MAŁGORZATA MARKIEWICZ

as BOOK RAIDER

“As all historians know, the past is a great darkness, and filled with echoes. Voices may reach us from it; but what they say to us is imbued with the obscurity of the matrix out of which they come; and try as we may, we cannot always decipher them precisely in the clearer light of our day.

(Applause.)

Are there any questions?”

The above quotation ends the Historical Notes on the Handmaid’s Tale, the epilogue of Margaret Atwood’s feminist dystopia. The notes, an incomplete (sic) transcript of a scientific conference held in an even more distant future, are an extraordinary thing. Written in a nearly humorous tone utterly different from the whole novel, it not only brackets The Handmaids’s Tale, but places it in a completely different order. The book we have just read turns out to be not so much a vision of the future, a dark prophesy, as a document from the past. A written and recorded account of a nameless victim of a theocratic regime found in the ruins of the city of Bangor. So the nightmare is over. Women are free again. Gilead has fallen. It can be the subject of study and scientific debates. Actually we feel relieved. Even though none of this has happened yet, if it could ever have happened.

Show more

Incidentally, the book itself was supposed to be a relic of the fears of the conservatism of Reagan’s era. But it returned during Trump’s presidency as a television series adaptation. Set more in the here and now.

So The Handmaid’s Tale is a big problem. The future is the past, and the latter has replaced the present. The book has been turned into a film. Everything is supposed to be fiction, and yet it hurts as if it were real. It’s enough to drive you crazy.

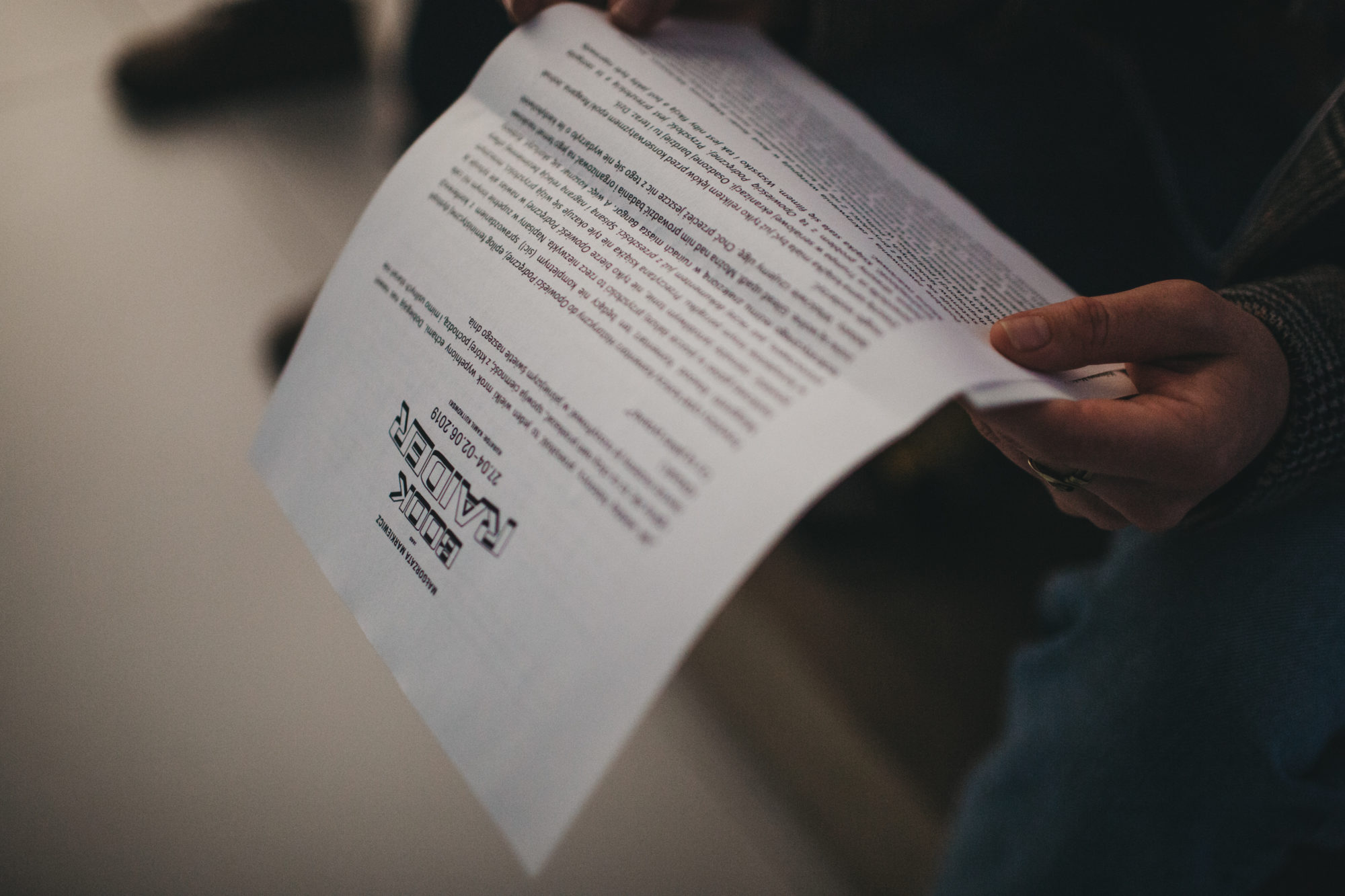

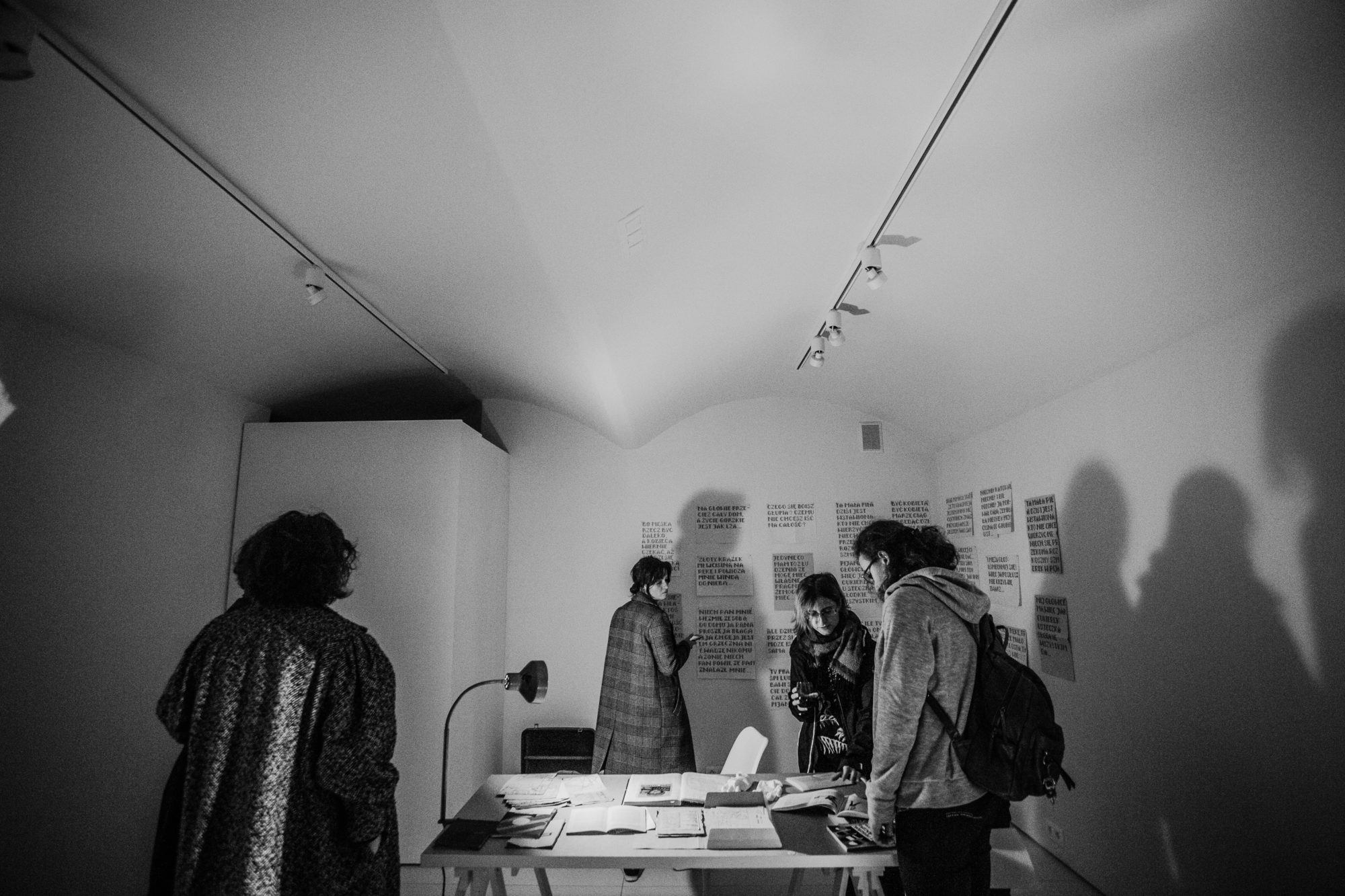

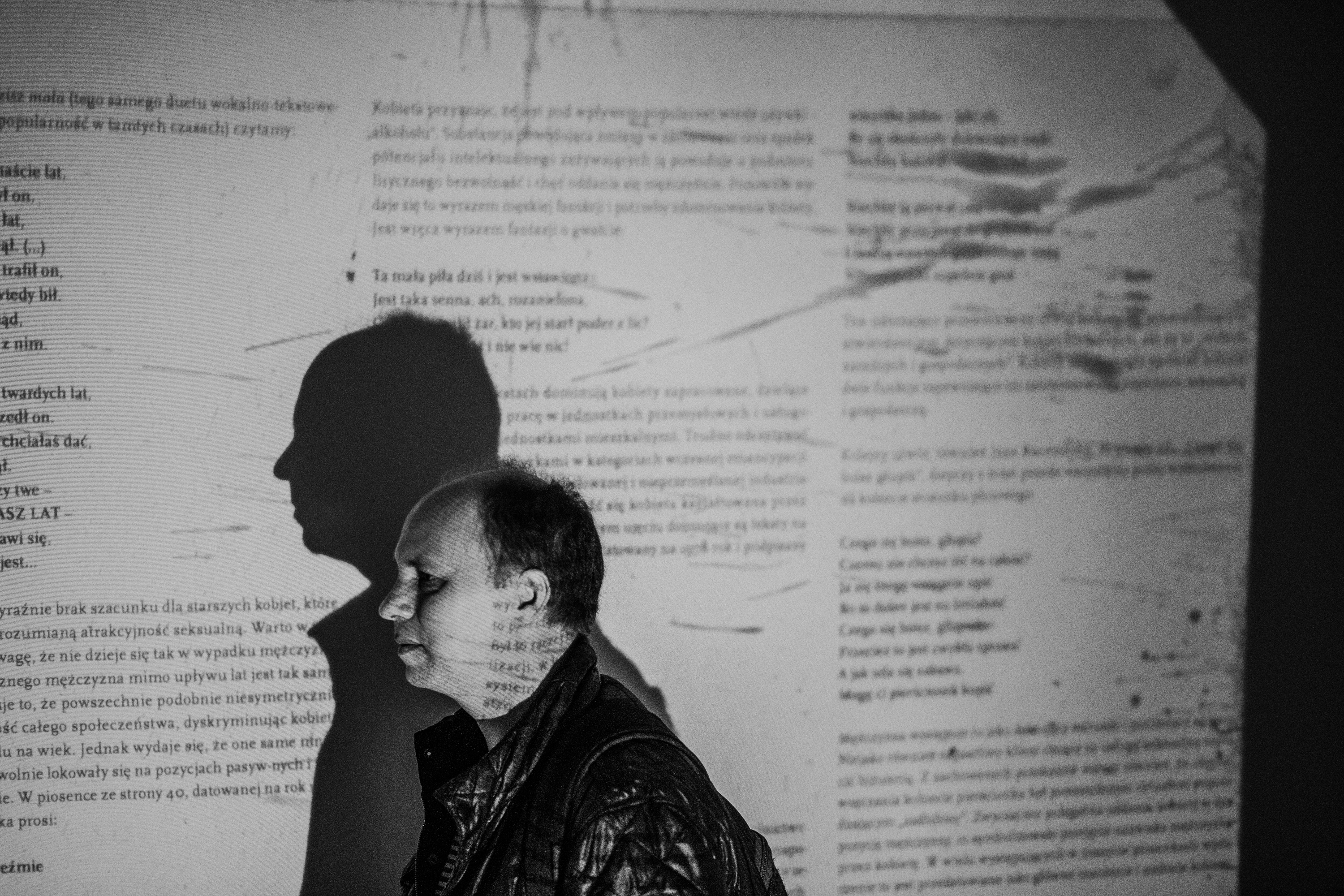

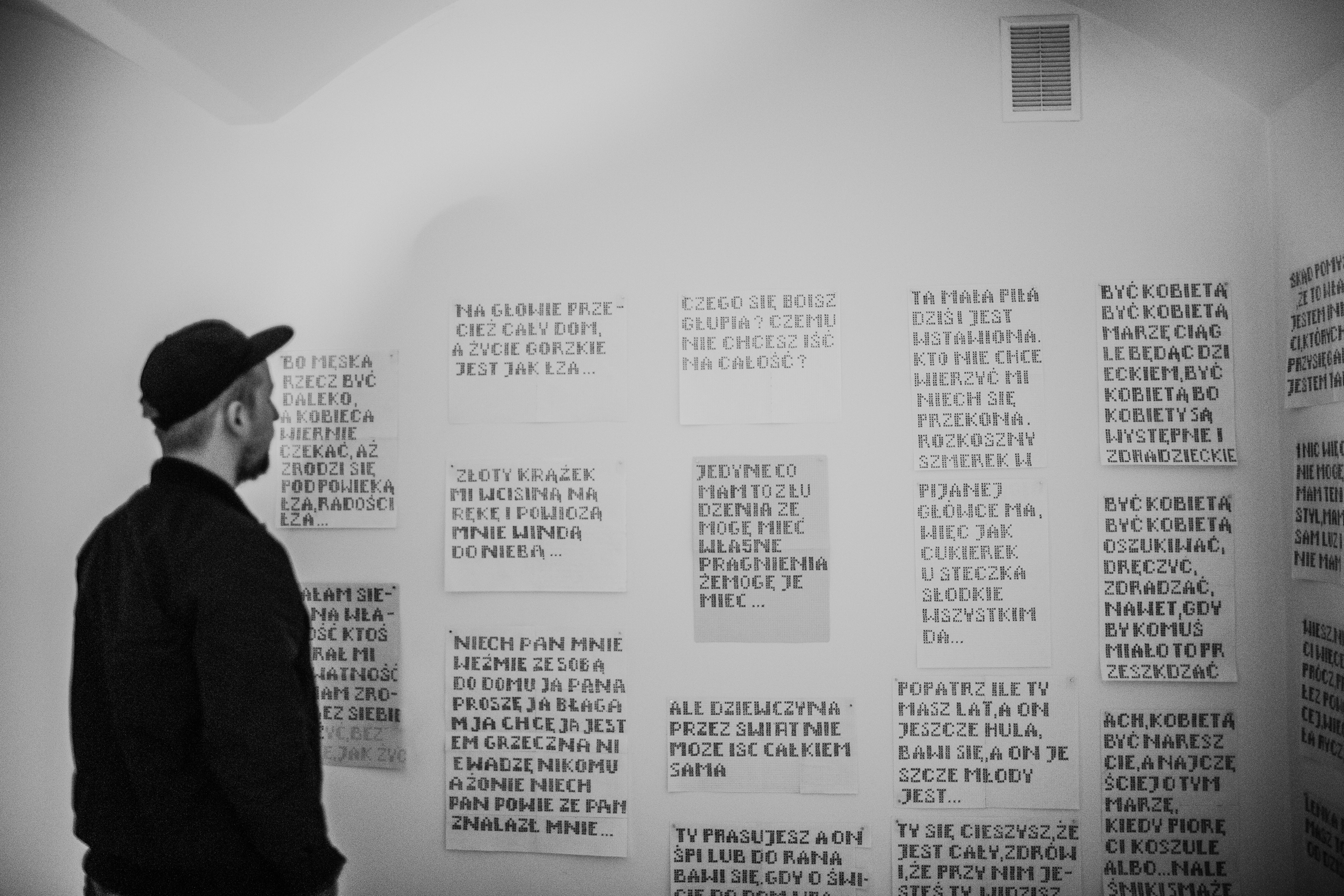

Similar twists and curvatures occur in Book Raider by Małgorzata Markiewicz. The exhibition turns out to be a story from the future. From a somewhat indeterminate world after the „Great Collapse” of the existing social and political systems and the establishment of completely new ones that are free of the current divisions and disproportions. In this reality a nameless (again) female Anthropologist, a character played by the artist, finds relics of the past that is our present: a notebook filled with lyrics of Polish 20th-century pop songs, an embroidered dress and fragments of Robert Altman’s film 3 Women. She begins a strange investigation, analyses texts and video material, and talks to the “last old woman”. The project closes with a scientific article (a bit like the one in the introduction to Stanisław Lem’s Memoirs Found in a Bathtub) on the condition of women in the 20th century. On the misogyny, sexism and discrimination hidden in the songs’ lyrics. Her surprise gives way to indignation, which turns into a little madness. The parascientific method gives rise to a dream of revenge using a gun, in which a playing card known colloquially as Dupek (Polish for “asshole” or “jerk” and a common term for jack) symbolises the phallus (exactly like the one in the form of a neon sign in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks).

On the other hand, perhaps the method is not parascientific at all, but is more of a feminist strategy of archival research (following an idea of the philosopher Ewa Majewska). A different strategy, which hacks and turns the patriarchal “scientificity” inside out. Maybe this method is legitimate in the Anthropologist’s world, maybe it’s the only one.

Book Raider turns out to be a science fiction exhibition strongly rooted in pop culture, and like every story of this kind is not so much a fable about the possible as the sum of current fears, problems and questions. The fictional distance of time makes it possible to emphasize, define or experience them in a safe futuristic costume. The very title is also popcultural. Book Raider is obviously a reference to Tomb Raider and Lara Croft. Once the greatest icon of the video game industry (and the protagonist of a series of comics and films spawned by her popularity). The armed archeologist, “Indiana Jones in a skirt”, or rather skimpy shorts, is also an interesting example of how thinking about femininity has changed over the last twenty years. Originally conceived more as a sex object for the male eye, she has gone on to become a multidimensional and full-blooded heroine.

The structure of virtual reality is also present in the exhibition. According to Mieke Bal, an exhibition is not really different from a film. It always has or ought to have a cinematic narrative and the works in an exhibition are or ought to be individual scenes of a film. The cinematicity is constructed wholly through the eyes of the spectator. But in Book Raider things are a little different. The exhibition is constructed around a short video in which we meet the Anthropologist (played by the artist) and participate in her finding of the notebook with the songs, here research and her dream. The film and the exhibition are intertwined. They become both at the same time. The fourth wall is destroyed and the viewer is invited to step inside. Into the protagonist’s office/laboratory and the happening that takes place on the opening night, during which you can shoot a ball of coloured paint at an outsized playing card (as in Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, a bit as in a computer game, and a little like Niki de Saint Phalle shooting at her paintings). And though the show is accompanied every now and then by the sounds of the emancipation song You Don’t Own Me by Lesley Gore, this act of controlled entertainment violence may, like some opening nights, leave you with a hangover. Because realising the continuing unequal status of women should definitely leave you with one.

Are there any questions?

Kamil Kuitkowski

Photograph: Grzegorz Mart

Show less