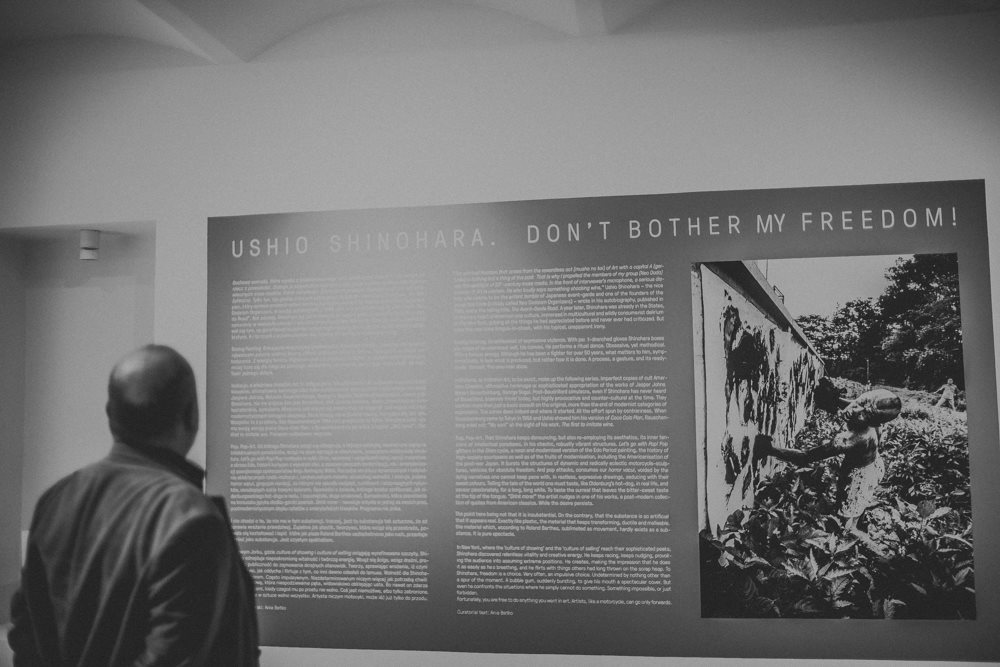

“The spiritual freedom that arises from the rewardless act [musho no koi] of Art with a capital A [geijutsu] is nothing but a thing of the past. That is why I propelled the members of my group [Neo Dada] into the spotlight of 20th-century mass media. In the front of interviewer’s microphone, a serious discussion of Art is useless. He who loudly says something shocking wins,” Ushio Shinohara, the nice boy, who seems to be enfant terrible, of Japanese avant-garde and one of the founders of the group Neo Dada (initially called Neo Dadaism Organizers), wrote in his autobiography, published in 1968, under the telling title, The Avant-Garde Road. A year later, Shinohara was already in the States, at the very heart of American pop culture, immersed in multicultural and wildly consumerist delirium of the 70s New York, gulping all the things he had appreciated before and never ever had criticized. But even this was done tongue-in-cheek, with his typical, unapparent irony.

Boxing Painting. An enthusiast of expressive violence. With paint-drenched gloves Shinohara boxes the areas of an enormous wall, his canvas. He performs a ritual dance. Obsessive, yet methodical. With a furious energy. Although he has been a fighter for over 50 years, what matters to him, symptomatically, is less what is produced, but rather how it is done. A process, a gesture, and its ready-made. Himself. The one-man show.

Show more

Imitations, or Imitation Art, to be exact, make up the following series. Imperfect copies of cult American Classics, affirmative hommage or sophisticated appropriation of the works of Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, George Segal. Post-Baudrillard simulacra, even if Shinohara has no idea who Baudrillard is, bizarrely trivial today, but highly provocative and counter-cultural at the time. They contain more than just a basic assault on the original, more than the end of modernist categories of expression. The series does indeed end where it started. All the effort spun by contrariness. When Rauschenberg came to Tokyo in 1964, Ushio showed him his version of Coca Cola Plan and Rauschenberg cried out: “My son!” at the sight of his work. The first to imitate wins.

Pop. Pop-Art. That Shinohara keeps denouncing, but also re-employing its aesthetics, its inner tensions of intellectual paradoxes, in his chaotic, robustly vibrant structures. Let’s go with Pop! It glitters in the Oiran cycle, a neon and modernised version of the Edo Period painting, the history of high-society courtesans as well as of the fruits of modernisation, including the Americanisation of the post-war Japan. It burst the structures of dynamic and radically eclectic motorcycle-sculptures, vehicles for absolute freedom. And it attacks, consumes horror vacui, voided by the dying narratives one cannot keep pace with, in restless, expressive drawings, seducing with their sweet colours. Telling the tale of the world one must taste, like Oldenburg’s hot-dog, in real life and passionately savour, for a long, long while. To taste the surreal that leaves the bitter-sweet taste at the tip of the tongue. “Drink more!” the artist nudges in one of his works, a post-modern collection of quotes from American classics. While a desire persists.

The point here being not that it is insubstantial. On the contrary, that the substance is so artificial that it appears real. Exactly like plastic, the material that keeps transforming, it is ductile and malleable, the material which, according to Roland Barthes, sublimated as movement, hardly exists as a substance. It is pure spectacle.

In New York, where the ’culture of showing’ and the ‘culture of selling’ reach their sophisticated peaks, Shinohara discovered relentless vitality and creative energy. He keeps racing, keep nudging, provoking the audience into assuming extreme positions. He creates, making the impression that he does it as easily as breathing, and he flirts with things others had long thrown on the scrap heap. To Shinohara, freedom is a choice. Very often, an impulsive choice. Undetermined by nothing other than a spur of the moment. A bubble gum, suddenly bursting, to give his mouth a spectacular cover. But even he confronts situations where he simply cannot do something. Something impossible, or just forbidden.

Fortunately, you are free to do anything you want in art. Artist like a motorcycle, can go only forwards.

Curatorial text: Ania Batko

Curators: Marta Błachut, Lucyna Shefter

Arrangement design: Marta Dymitrowska

See artists:

Noriko Shinohara >

Ushio Shinohara >

Show less